SCOTUS Vote Analysis

Inspired by the analysis of Sarah Isgur and Dean Jens over at Politico, I thought it'd be nice to have access to the same analysis for different SCOTUS terms.

Inspired by the analysis of Sarah Isgur and Dean Jens over at Politico, I thought it'd be nice to have access to the same analysis for different SCOTUS terms.

This is a visualization of votes on the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) from 1946-2022. The goal is to see if and how Justices on the Court appear to relate to one another – do they form voting blocs, and if so, do they appear meaningful?

This work is replicating work done by Sarah Isgur and Dean Jens in their Politico piece that discussed Isgur's 3-3-3 court theory for the 2022 term. Additionally, this allows you to view similar analysis for different years (back to 1946).

The Supreme Court Database curated by Washington University Law proved to be an invaluable resource and powers this visualization. This work uses their Justice Centered data from the 2023 Release 01, covering the 1946-2022 terms. For all decisions available, I used the "majority" variable (i.e., whether a Justice was in the majority/minority) to define groupings for individual cases.

SCOTUS experts, I know this is a massive simplification (e.g., concurring in part and dissenting in part, spicy Alito concurrences, etc.), but my expertise is statistics, not SCOTUS analysis. Want to look at a different construction? You can find the code here to start you off, or reach out.

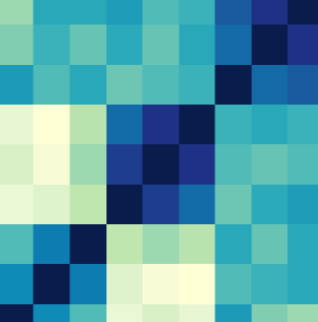

The first plot is a heatmap, showing how likely each Justice was to be in the same group as any other for that term (i.e., were they in the majority/minority together, or not). The ordering of Justices generally shows groupings (like 2022's 3-3-3 Court) by identifying blocs of Justices who vote similarly. This is an automated process based only on agreement/disagreement with other Justices with no notion of Justice's ideology or the politics relevant in each decision.

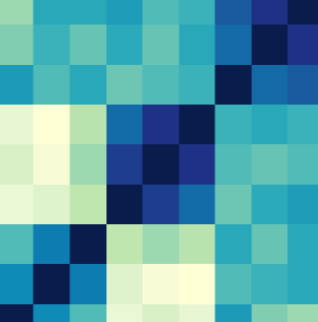

The second plot is a visualization to help observe the variation we see in votes. The specific values aren't as meaningful as the patterns we observe. The horizontal axis should explain most of the variation, the vertical axis will explain a bit more. We could keep this going in 3D (or 4D, ...), but this should let us see the broad patterns. The left-right (or up-down) placement of each Justice is an artifact of the algorithm and doesn't necessarily correspond to things like ideology. Again, this is determined only from whether Justices agreed or disagreed with each other on particular decisions, with equal weight to all decisions.

As a technical note, this is a scatterplot of the first two columns of the U matrix from a singular value decomposition of the heatmap data.

Let's take a look at the 2022 example, where we see Sarah Isgur's now-famous 3-3-3 Court. As discussed in the Politico piece and elsewhere, the 2022 Court appears to have three blocks of three Justices each, breaking the 6 conservative-appointed Justices into two blocs – the high and low institutionalists.

The first plot shows how often Justices voted with one another. We see that just by how often Justices voted with or against each other, they tend to fall into three blocs:

Bloc 1: Justices Barrett, Kavanaugh, and Roberts

Bloc 2: Justices Alito, Gorsuch, and Thomas

Bloc 3: Justices Kagan, Jackson, and Sotomayor

We can see, for example, that members of each bloc tend to agree with each other more than they agree with the other 6 Justices. We also see that Blocs 2 and 3 tend to disagree with each other more than Blocs 1 and 2 or Blocs 1 and 3.

As for the scatterplot, SCOTUS experts have assessed the horizontal axis of the second plot as roughly aligned with "institutionalism" (left being more institutional, right being less) while the vertical aligns with "ideology" (up being more conservative, down being more liberal). Again, the statistical technique at play here knows nothing of politics, judicial philosophy, or anything of the sort. But, it happens to be that when trying to explain differences between how Justices vote, we find that familiar, understandable explanations map well onto the analysis.

Moving to different terms, these axes will need entirely new explanations -- even just moving to 2021, the horizontal may correspond to an entirely different explanation. The meaning (if indeed there is one) is best left to the SCOTUS experts.

In addition to looking at the percent agreement of Justices, you can also look at the number of times they voted together. This technique struggles when Justices do not sit the full term (the incoming or outgoing Justice is often in a "bloc" alone).

Finally, as a footnote to Advisory Opinions listeners (we really need a name – AOers?), processing the data from the Supreme Court Database took longer at first then started to speed up as it moved from the '40s to the most recent data. Why? Because SCOTUS is deciding fewer cases. Faster code: the one upside to a slowing Court, I guess.